Mathematical Logic Course

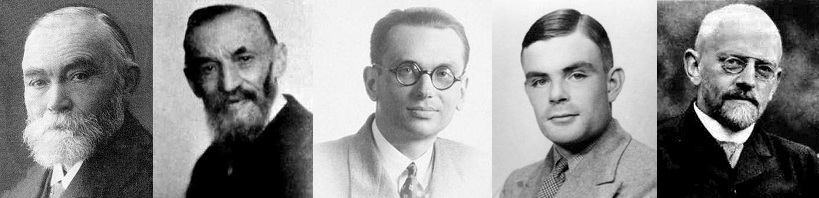

Historically, the existence of mathematical entities came to be justified by the physical world which they purported to represent. But as the concepts introduced in the 18th and 19th century became ever more abstract and divorced from physical reality, the imperative grew to fashion a system of formal reasoning capable of justifying their existence. This and several other factors contributed to the birth of formal mathematics at the end of the 19th century. Cantor had just pioneered techniques for studying infinite collections, Frege introduced quantification into logical reasoning, and Peano proposed an axiomatization of number theory. In the next few decades, Frege’s logical system had morphed into first-order logic and Zermelo’s axioms placed Cantor’s set theory on an axiomatic foundation. First-order logic became a front runner for a universal language of mathematics and the apparent success of the axiomatic method had encouraged mathematicians to believe that an indisputable formal foundation for mathematics was finally within reach. Spearheaded by David Hilbert, the campaign to formalize mathematical thinking had two main goals: to introduce axiomatic foundations for various mathematical disciplines and to develop finitary meta-mathematical methods capable of demonstrating that the proposed axioms were consistent (non-contradictory) and complete (could prove every statement or its negation). At the same time, foreshadowing the advent of the computer, mathematicians began to examine the notion of effectively computable functions.

The course will cover formative developments in the field of mathematical logic that occurred roughly in the period 1930-40. We will start with the Completeness Theorem, proved by Gödel in 1929, demonstrating that formal theorems of a given theory are precisely the statements true in all its models, and thus uniting the notions of formal provability and semantic truth. The highlight of the course will be Gödel’s First and Second Incompleteness theorems, proved in 1931, that brought an end to Hilbert’s program and drastically changed the course of formal mathematics. The first Incompleteness theorem showed that any reasonable axiomatization of number theory or a discipline extending it must be incomplete, while the Second Incompleteness theorem showed that the consistency of such an axiomatization cannot be established by finitary means. We will prove the Incompleteness theorems using a model theoretic perspective via nonstandard models of Peano’s axioms, whose theory we will spend a substantial portion of the course developing. We will encounter our first model of computability, the recursive functions, in the analysis of the Incompleteness theorems. The course will end with the second model of computability: Turing machines and the beginnings of computability theory.

Topics

- The Completeness Theorem

- Models of Peano Arithmetc

- Recursive Functions

- First Incompleteness Theorem

- Second Incompleteness Theorem

- Turing Machines

- Tennenbaum's Theorem

Literature

- Course Logic Notes by Victoria Gitman

- Models of Peano Arithmetic by Richard Kaye

- Logic of Mathematics by Zofia Adamowicz and Paweł Zbierski

- Introduction to Mathematical Logic by Elliot Mendelson

- Computability Theory by S. Barry Cooper