An introduction to nonstandard models of arithmetic

This is a talk at the Virginia Commonwealth University Analysis, Logic and Physics Seminar, April 24, 2015.

Slides

"... the point of philosophy is to start with something so simple as not to seem worth stating, and to end with something so paradoxical that no one will believe it." -- Bertrand RussellEpistemology is a branch of philosophy dealing with how we know that something is true. Broadly speaking, mathematical epistemology is encompassed in the axiomatic method: we know that a mathematical assertion is true if it can be derived by logical inference starting from a collection of fundamental properties, called the axioms. Euclid introduced the axiomatic method in his treatise on geometry, Elements, around 300 BC. But a complete formal treatment of mathematics had to wait another two millennia, which is about the same time that it took for someone to finally write down the axioms of arithmetic! In 1889, Giuseppe Peano, building on an earlier work of Dedekind, proposed an axiomatization of arithmetic. The Peano axioms summarize what every high school student knows about the natural numbers: addition and multiplication is commutative and associative, together they obey the distributive law, 0 is the additive identity and 1 is the multiplicative identity, the ordering is discrete and respects both addition and multiplication, and, most importantly, the principle of induction of holds. Peano's axiomatization of arithmetic was one of many developments in the newly established field of formal mathematics. More than two millennia after Euclid's revolutionary conceptualization, the increasingly abstract character of mathematical advances in subjects such as analysis made it imperative for mathematicians to begin developing a formal framework. The notion of function in analysis slowly morphed from a mapping given by an explicitly stated rule to an arbitrary collection of ordered pairs satisfying the property of being a function. At that point, obviously some rules needed to be imposed about which types of collections exist, leading naturally to early attempts to axiomatize set theory.

The axiomatic method, as conceived for most of the two millennia leading up to the critical developments in formal mathematics in the 20th century, was the view that all properties of a mathematical structure, say the natural numbers, can be proved from a correctly chosen collection of axioms. The axioms themselves were truths so self-evident that they did not require a proof. The intention was also to have the axioms determine the structure in question up to isomorphism. In this simple universe, the natural numbers would be the only structure satisfying the Peano axioms and every true arithmetical statement would be provable from them.

The 20th century saw a rapid succession of fundamental developments in formal mathematics. Many of them could be interpreted as demonstrating the limitations of the formal approach, but rather they revealed its hidden complexity. Cantor developed a theory of infinite collections and Zermelo codified its properties in his axiomatization of set theory. Led by Skolem, first-order logic was developed as a powerful and robust language of formal mathematics. The Lowenheim-Skolem theorems showed that a collection of axioms cannot determine the size of a model: every collection of axioms having an infinite model, also has models of every infinite cardinality. (A model for a collection of statements is simply a mathematical structure in which the statements hold true.) Gödel (and Maltsev) proved the completeness theorem showing that every collection of statements from which no contradiction can be derived has a model. A powerful consequence of this, the compactness theorem, showed that if every finite fragment of a collection of statements has a model, then so does the entire (no matter how infinitely large) collection. Finally, Gödel's first incompleteness theorem showed that the Peano axioms, and in fact any reasonable axiomatization of arithmetic, could not prove all true arithmetic statements.

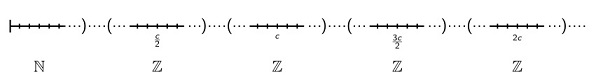

It already follows from the Lowenheim-Skolem theorems that there are uncountable models of the Peano axioms. Yes, there are uncountable structures in which induction holds! Let's call the natural numbers the standard model of the Peano axioms and all other models nonstandard. An easy application of the compactness theorem shows that there are countable nonstandard models of the Peano axioms, or indeed of any collection of true arithmetic statements. Order-wise, these models look like the natural numbers followed by densely many copies of the integers: $\mathbb N$ followed by $\mathbb Q$-many copies of $\mathbb Z$ (see the slides for explanation).

Can we compute inside a nonstandard model of arithmetic? This question can be made precise in the following way. We can naturally think of elements of a countable nonstandard model as $\mathbb N\cup \mathbb Q\times\mathbb Z$. We already know how to add a natural number $n$ to a number $(p,m)$ sitting in some block $p\in \mathbb Q$: we get $(p,m+n)$. Is there a nonstandard model, where we would have an algorithm for figuring out $(p,m)\cdot n$, or even better $(p,m)+(q,n)$ and $(p,m)\cdot (q,n)$? But we cannot! Tennenbaum famously showed in 1959 that there is no countable nonstandard model for which there is an algorithm to compute any of the above (see this post). The proof boils down to the fact that every countable nonstandard model codes in some algorithmically undeterminable subset of the natural numbers and being able to compute $(p,m)\cdot n$ would give us an algorithm to determine which numbers are in that very complicated set. So finally we have that the natural numbers are unique in one sense, it is the only model of the Peano axioms in which we can compute.

There are continuum many non-isomorphic countable models of arithmetic and they have some remarkable properties. For instance, Friedman showed in 1973 [1] that every countable nonstandard model of arithmetic is isomorphic to a proper initial segment of itself. Whatever happens in a nonstandard model of arithmetic has already happened before! Also, while the natural numbers obviously have no nontrivial automorphisms, there are countable nonstandard models with continuum many automorphisms. In particular, a nonstandard model of arithmetic can have indiscernible numbers that share all the same properties. Indeed, the automorphism groups of nonstandard models have some remarkable properties themselves (for details, see [2]). What are the nonstandard models of arithmetic good for? While Gödel showed that there are true arithmetic statements that cannot be proved from the Peano axioms, the example he demonstrated is not something a number theorist would encounter in their everyday practice. Using the structure of nonstandard models of arithmetic, Kirby and Paris in the 1980s developed techniques to show that interesting purely number theoretic statements such as Goodstein's theorem and the Paris-Harrington theorem cannot be proved from the Peano axioms [3]. Maybe the day will come when we are able to show using nonstandard models of arithmetic that ${\rm P=NP}$ cannot be proved from the Peano axioms! Always nice to end on an impossible note.

References

- H. Friedman, “Countable models of set theories,” in Cambridge Summer School in Mathematical Logic (Cambridge, 1971), Berlin: Springer, 1973, pp. 539–573. Lecture Notes in Math., Vol. 337.

- R. Kossak and J. H. Schmerl, The structure of models of Peano arithmetic, vol. 50. The Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006, p. xiv+311.

- L. Kirby and J. Paris, “Accessible independence results for Peano arithmetic,” Bull. London Math. Soc., vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 285–293, 1982.